Employee engagement remains a hot topic among organizational leaders and consultants, and is often regarded as an upstream indicator of organizational performance. Gallup’s nationwide survey of employee engagement found the percentage of U.S. employees engaged in their jobs averaged 31.5% in May 2015—about the same as for the year 2014. This result is of concern because it’s assumed that engaged employees are “involved in, enthusiastic about and committed to their work” and are “strongly connected to business outcomes essential to an organization’s financial success, such as productivity, profitability and customer engagement”1.

With an estimated $720 million being spent annually on engagement2, why are these numbers so low? And why have some organizations found that, even when they have at least temporarily increased engagement, performance has not improved? More generally, what can leaders and consultants do to effect sustainable improvements in engagement and performance?

Engagement and Performance: The Traditional Perspective

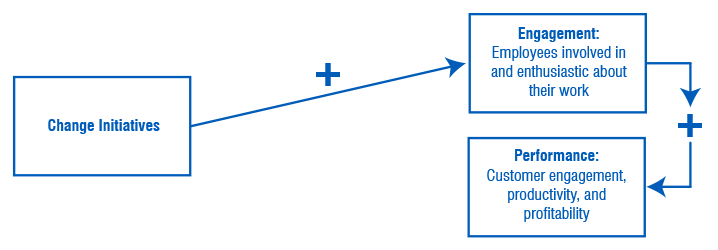

When these types of questions arise, it’s useful to take a step back and clarify what we’re talking about. Over the past decade, it has generally been assumed that we can improve engagement by, for example, introducing changes in the way managers manage, clarifying job expectations, and improving communication. In turn, because certain studies have shown a correlation between engagement and performance indicators, it is assumed that an increase in engagement will lead to better performance.

The diagram above illustrates these relationships, highlighting the positive impact of increased engagement on outcomes such as customer engagement, productivity, and profitability. The “change initiatives” typically focus on the factors mentioned above (like management styles and communication) as well as other climate-type variables measured by many engagement surveys. While simple and intuitively appealing, interventions based on the relationships shown do not consistently produce fruitful results.

On Culture vs. Climate

The limitations of this approach have been noted by many consultants, including Diane Stuart, formerly an internal Organizational Performance Consultant with Advocate Health Care and now an independent consultant. Stuart was tasked with increasing and stabilizing engagement in a high-profile, semi-autonomous unit of her organization. Initial engagement data came from a regularly administered climate survey, which generated inconsistent results and pointed to the need for a deeper assessment.

As Stuart states in a recent case study: “The climate survey would show low engagement. There would be a flurry of activity which would improve results temporarily, but they would drop back down again. It was clear they had to work on the behavioral norms that were hindering the development of the strong relationships necessary for effective employee engagement.”

The “behavioral norms” referenced by Stuart are a central component of organizational culture rather than climate and have been shown in studies dating back to the turn of the century to have a stronger impact than climate on outcomes3.

Questioning Tradition

Beyond the need to add culture to the equation, the assumed relationship between engagement and performance embedded in the traditional perspective is questionable. Whereas certain studies indicate that engagement measures are positively correlated with measures of performance, the nature and direction of the relationship is debatable. In An Idiot’s Guide to Employee Engagement, Edward E. Lawler notes: “In many cases, however, the data are misinterpreted, misunderstood, and result in wasted time and money…. The results [of studies carried out over the decades] consistently showed low or no correlation between the two. In some cases, there was low correlation only because performing well made employees more satisfied, not because employees worked harder because they were satisfied.”

In other words, even though performance might be related to factors like satisfaction and engagement, the causal relationship could be the opposite of what is traditionally assumed. Performance can lead to engagement rather than vice versa because of the intrinsic rewards of doing a good job or the rewards provided by superiors (e.g., more interesting assignments, greater autonomy, recognition). Alternatively, correlations between engagement and performance might be observed because they are both influenced by a particular contextual factor—such as enriched jobs that offer variety as well as norms and expectations that encourage achievement. These alternative interpretations for widely reported research results on engagement suggest that the traditional perspective needs to be updated.

Changing Culture to Improve both Engagement and Performance

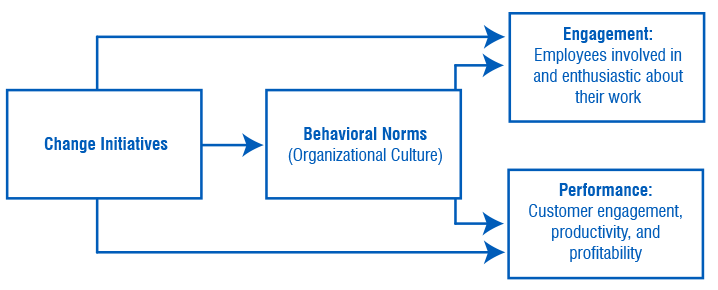

Referring again to the change initiative at Advocate, Stuart fundamentally added another element to the equation—behavioral norms—and reframed engagement and performance as outcomes of culture. The target for change became the culture of the unit:

Ineffective working relationships had both passive and aggressive components. In a blaming culture there is little ownership for individual contributions to problems. Teams that display passive and aggressive behavioral norms don’t easily recognize the way those habits and behaviors harm relationships within the team. Behaviors are so ingrained in deflection that members don’t see the impact they’re having on the group as a whole.

A series of change and development activities—focusing on leadership, group processes, communication, and feedback—were initiated, all designed to move the culture toward Constructive and productive norms and away from Defensive and counter-productive norms. (Click here for an interactive explanation of the Constructive and Defensive styles.) In a three-year period, the unit effected a significant shift in its culture leading to better communication, increased engagement, and important business outcomes.

For Real Results, Measure Culture

This and other case studies support the above-mentioned research findings that culture has a greater and more consistent impact on outcomes than does climate. Climate surveys can play a valuable role in identifying change initiatives, but those levers must be selected in consideration of their likelihood of accentuating and reinforcing organizational values and the type of operating culture that organizational members view as ideal. Levers for change must be selected also in consideration of the outcomes desired and valued by members. If both engagement and specific performance outcomes are goals, the change initiatives selected (whether focusing on systems, structures, job design, or people) should be those that have the potential of simultaneously improving the former as well as the latter.

As shown in the model below, the most reasonable way to proceed is to implement changes that simultaneously promote both engagement and performance rather than hoping that an improvement in one will lead to an improvement in the other.

Make Culture your Centerpiece

More generally, this updated perspective on engagement and performance suggests that culture should serve as the “centerpiece” when thinking about and planning activities for enhancing engagement. Doing so requires that organizational members identify the performance outcomes and goals (in addition to engagement) desired, visualize the type of culture that would enable the organization to reach those goals, and implement change initiatives supportive of those outcomes both directly and indirectly via culture.

Article also co-authored by Cheryl Boglarsky and Meghan Oliver

1 Adkins, Amy. (2015, June 9). U.S. Employee Engagement Flat in May. Gallup. Retrieved from http://www.gallup.com/poll/183545/employee-engagement-flat-may.aspx.

2 Kowske, Brenda. (2012, August 14). Employee Engagement: Market Review, Buyer’s Guide and Provider Profiles. Bersin & Associates. Retrieved from http://www.bersin.com/engagement-market-review.

3 Glisson, C. & James, L.R. (2002). The cross-level effects of culture and climate in human service teams. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 23 (6) 767-794.